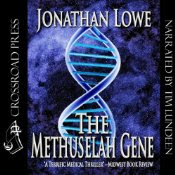

From the Vault: Tim Lundeen’s career in audiobooks has encompassed most aspects of the business, including narration of both fiction and non-fiction across multiple genres. Both national and international publishers have found his low key narration style captivating to their listeners. He has also directed and edited authors Gary Chapman, Shannon Ethridge, Nate Larkin, Andy Andrews, Elizabeth George, Michelle McKinney Hammond, Louie Giglio, Joel C. Rosenberg, among others, (and my novel The Methuselah Gene for Crossroad Press.) Tim and his family live in a suburb of Chicago, IL.

Jonathan Lowe) As a family man from Chicago, how did you come to narration? What influenced you?

Tim Lundeen) I was the tech/audio/lights/catwalk guy for the school theater, with a tiny bit of acting in high school and college, so I was around the storytelling and character work, while also being comfortable with the minimal technology of on-stage productions, like a soundboard and various microphones. A fellow actor in college invited me to a multicast audio production that needed some extras, and it felt right. . . challenging, with a mix of acting and technology, and thankfully no memorizing. Just before I graduated college I was offered a job for a print publisher, but I turned them down, saying I was interested in audio/studio publishing work. They directed me to an audio book production company in the area, which had me convert old reel-to-reel stuff to digital format for either cassette or CD mastering. Then I edited some narration, engineered some recording sessions, and eventually produced/directed other voice talent through full-length audio book productions. It wasn’t even the recording sessions that inspired or influenced me most, but the opportunities I had to take the various voice talent out to lunch. I might be producing the same voice talent all week, so getting to know these actors outside of the studio was crucial for me, in directing my efforts toward an effective voiceover career.

Q) Being an engineer and a producer, you’re into most aspects of audiobook production. What makes for a great production?

A) Assuming the writing is good, it’s my opinion that the words on the page should be dictating how we narrate. Discerning that dictation could be called the “interpretation of literature,” which is an internal, cognitive, mental exercise. Properly interpreting the words on the page isn’t verbal, it doesn’t happen as I’m narrating. Ideally it would be happening subconsciously, before I even open my mouth. Of course the more well-read we are, the more familiar we’ll be with language and vocabulary in general, and the greater our sense of properly interpreting the printed word. But narration involves imagination and creativity to properly convey those printed words to the listening audience. A “great production” results in a listener who fully experiences the words that author has written, the point being made, the message being shared, or the story being told. The sooner I get out of the way as the voice talent, the better.

Q) You’ve also done Christian audio in various genres like suspense, and non-fiction like the “Anne Frank Remembered” bio that earned an Audie award. What is most difficult, and why?

A) The most difficult to produce, even when I’m not the narrator, is a Christian fiction title that has no substance. I’ve just experienced titles by honest and sincere believers who feel they have a purpose or meaning to the stories they tell, but it’s almost like they’re afraid to push deeper into their own God-given skills to draw out the very best of their writing capabilities. The really tough stuff is in theological non-fiction or the personal-health / medical genre. Fiction story-telling is a walk in the park, compared to keeping all the Greek and Hebrew pronunciations straight or quadruple checking the phonetic accuracy of pharmaceutical terminology. First century proper nouns have a little flexibility, but I could be putting someone’s life at risk if I mispronounce a medical term. Especially when sites like Amazon.com mistakenly list me, the narrator, as the co-author of an audiobook. That’s scary!

Q) Industry peers mention your own “low key” narration style, which tends to avoid melodrama and gives a natural approach to listening, making the actor himself disappear behind the words. That’s always a goal, but I’m wondering how differently you approach fiction, and how you direct other narrators, utilizing their own set of talents.

A) Want to hear a cheesy analogy? If I’m canoeing down the Mississippi River, sometimes it’s fast and sometimes it’s slow, sometimes it’s choppy, and other times calm, and sometimes it’s murky. Well, it’s always murky. But regardless of the temperament of the water, it’s always the Mississippi River. In storytelling, the voice of the narrator is that river, carrying the listener along the journey. So I never forget the journey the listener is on. The listener is never in control over how that water is moving, and that lack of control can make them struggle to pay attention (at best) or just become disinterested (at worst) and hop off at the next port. But they’ll want to keep listening if there’s a reassuring undercurrent, that the story is still flowing, and moving in the right direction. I believe the voice of the narrator in a story is what makes the listener feel safe enough to want to hang on for the ride. When it comes to directing other talent, if the narrator knows what he or she is doing, I usually don’t do much. They have their own style and I’ll make sure they stay true to that. Now, if I’m producing a novice narrator, I still usually don’t do much. While I’d love to coach and mentor the talent through every paragraph of the book, I don’t have that luxury. That kind of guidance and practice should respectfully be handled outside of the recording session. To me, directing other voice talent, with their own skills and styles of narration, is like directing any other musical instrument. I can’t direct an oboe to sound like a clarinet, even if they’re made out of similar materials. I can help them feel comfortable and confident in their own level of performance, maybe even help them sound better than they would have on their own, but I cannot perfect them. By the way, want to know the difference between a violin and a viola? One burns longer.

Q) Any anecdotes to share from the production booth? What’s the most interesting thing that’s happened, and who do you wish you could get in front of a microphone?

A) I was working on some analog conversion project in studio B, while studio A was producing Barbara Rosenblat on some fiction title. During one of the breaks, I went over and introduced myself as “just one of the ‘lackeys’ at the studio.” To which she said, “you don’t seem to be lacking much to me.” Once I was producing an author, reading her own book, and half way through the session that day we had to stop. She had her own radio show and was determined to host it. All we had was a phone patch, so she called into her own show and handled the topic of that day and other callers. She also went through a case and a half of water bottles, and a lot of bathroom breaks. It would be a blast to have Tim Curry in my studio. While most Hollywood actors are not voiceover talent at all, there are some great folks that would be fun to have in my studio, like Gary Sinise, Jon Voight, John de Lancie, etc. There are some Golden Voice audio book narrators that I’ve edited, though I’ve never had them in my studio. I would rather earn the right to meet them some day and buy them lunch, rather than host them at my studio. They do just fine in their own studios.

The Methuselah Gene novel (original small press hardcover from Five Star, 2010, then audiobook from Crossroad Press, 2014 and ebook.) Mentions Frank Muller lookalike. Predates discovery by real science of the use of a neutered HIV able to fight cancer, as of 2014 on Ron Howard’s Breakthroughs. Interviewed a Pfizer scientist and researched the plot: a pharmaceutical scientist is hacked and followed by a nefarious entity which steals his delivery formula and secretly tests it on a small town in Iowa. When it fails, and many die, they try to cover it up. Climax on cruise ship.

Frank Muller narrated my first novel, Postmarked for Death. He was Stephen King’s fav.

Frank Muller narrated my first novel, Postmarked for Death. He was Stephen King’s fav.